Sorry for the delay in updating this series about Chef and Jenkins. Last week I was busy celebrating with family and went through the Master’s hooding and commencement ceremonies. Unfortunately, I didn’t get a chance to revisit the blog until now.

This week I was getting acclimated to my new job at Cycle Computing. I am super stoked about this opportunity, and all of my Cycle colleagues seem like a friendly, and smart, bunch of people.

I wanted to get a few more thoughts from my Masters Capstone project into blog form. I want others to be able to learn from both the technical and theoretical side of my research. This post is distilled continuous integration theory applied to Chef cookbooks. Its not prescriptive, and it may not work for you. It was extremely effective in practice at Marshall, however.

Over a period of 12 weeks, there were 159 changes introduced into two cookbooks. There was a nominal failure rate of 19.2% to 20.31% in the continuous integration environment. The more realistic effective failure rate was actually 16.43% to 18.37% in the continuous integration environment. However, there was only a 0.99% to 1.92% rate of defect release for the in-scope software units over the course of the project.

Pipelines, background information

If you were at the community hack day for Chefconf, then maybe you already have seen some of this.

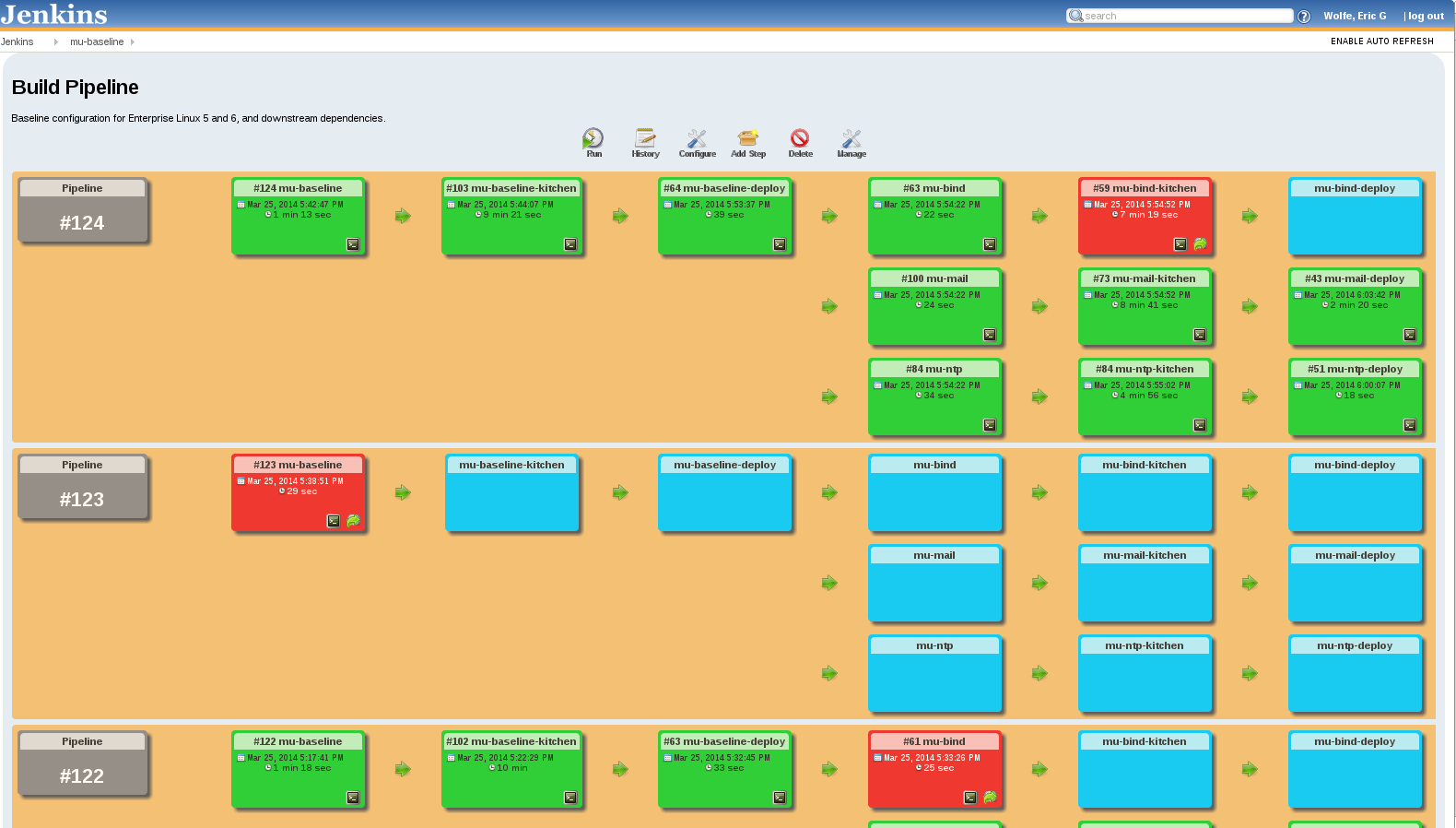

A continuous integration (CI) pipeline is a logical series of tests with upstream (afferent, or fan-in) and downstream (efferent, or fan-out) dependencies. The CI pipeline directional graph below shows the logical flow of the cookbook testing pipeline for an org-baseline and org-mail cookbook as roles that serve a business function to the organization. In the sense of a cookbook serving the purpose of a role in role-based configuration management. However not strictly, in the sense of Roles as defined in Chef vernacular, which is similar to a data structure.

The important takeaway is that if one uses a cookbook to serve the purpose of role-based configuration then this facilitates softare testing, and controlling the release of that software artifact into production. Chef Roles, or Data Bags could optionally be a part of that cookbook artifact utilizing Kitchen.CI with chef_zero as a provisioner. Those units of data do not, in and of themselves, make interesting software test cases. You could use something like BATS with Kitchen.CI to test the functional output of those data structures as they interact with recipe code.

In the pipeline directional graph, one can see that there are several build jobs aligned in order. My last post discussed constructing a touchstone build for quick running unit tests with Chefspec, and cookbook linting with Rubocop and Foodcritic. A touchstone build is a fast running, and fast failing, series of tests which are run first in a pipeline before any slower running integration tests.

We staged our cookbook pipeline into three stages at Marshall. Our role-specific cookbooks were staged into a fast touchstone build, a slower Kitchen.CI integration test build, and a Berkshelf deploy and constrain build. My next post will probably document some Kitchen.CI hacks to speed up, or otherwise improve, your cookbook integration process on Jenkins.

Upstream and downstream dependencies

The Jenkins Build Pipeline plugin will let one, have a simplified logical view of each continuous integration, or delivery, pipeline and all the upstream/downstream dependencies. One can specify a root point of reference, and Jenkins will show a pipeline view based on build jobs that trigger one another.

Here are some rough guidelines on building a cookbook pipeline considering upstream/downstream dependencies.

Upstream (afferent/fan-in) triggers

- Given there is a change in source control.

- At the minimum, a touchstone build job is triggered for the cookbook that changed.

- Given a locally maintained root project (baseline), or role cookbook.

- When there are locally maintained cookbook dependencies included, then they should trigger a build job on this root (baseline), or role, cookbook.

- When there are community maintained cookbook dependencies included, then there should be unit tests and integration tests to cover expected behaviours and guard against potential regression.

- Given a community maintained cookbook dependency.

- There is no build job locally, trigger is not required.

- Most likely not a role-specific cookbook. However, it can still be tested for expected behaviours in your dependent roles.

Downstream (efferent/fan-out) triggers

- Given any locally maintained cookbook.

- When something depends on this cookbook, then it should trigger a build job on any locally maintained cookbook dependent on it.

- Given a locally maintained root project (baseline) cookbook.

- When there are role-specific cookbooks dependent on it, then it should trigger every dependent cookbooks that fits/includes the specification of the baseline configuration.

- Given there is a deployment build job.

- When there is sufficient test coverage to provide confidence for release. Then the deployment build job blocks until any upstream dependencies have finished building, and have been fully integrated with any pending changes in the pipeline.

- Each role-specific cookbook should constrain its own role-specific environment to avoid deployment constraint race conditions.

Pictures >= Words

What the baseline pipeline actually looks like in Jenkins Build Pipeline plugin can be seen below. The baseline touchstone build triggers the Kitchen.CI build. The Kitchen.CI build job in-turn triggers a Berkshelf deploy, and constrain, into production environments. Each role-specific cookbook needs to have its own constrained environment. Otherwise, the DNS specific role could remove the environment constraint for the mail specific role, or vice versa. If one tried to constrain the same environment with multiple roles, then the last build job to finish wins.

What the upstream/downstream software dependencies actually look like to Berkshelf, or a Chef node, for an org-mail cookbook.

P.S.

I am extremely grateful for Jamie Winsor, Seth Vargo, and Michael Ivey’s work on Berkshelf; Seth Vargo’s work on Chefspec; Andrew Crump’s work on Foodcritic; Fletcher Nichol’s work on Kitchen.CI; Sean Porter’s work on Kitchen plugins. If it weren’t for the rich set of tools we have at our disposal for testing cookbooks, I really don’t know how I could have approached this Capstone project.

P.P.S

I find an academic style of writing very awkward and almost painful. I have read it so many times, I am sick of it, however.

If you must read it, here is the Capstone paper, and Defense presentation.